- Home

- Birkbeck, Matt

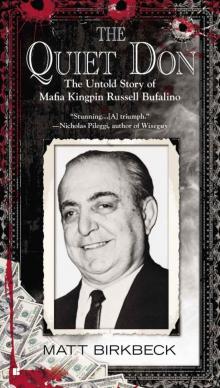

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino Read online

Praise for

DECONSTRUCTING SAMMY

“Birkbeck has killer leads, gripping kickers, and sensational descriptions. This cinematic book reads more like a detective story than a traditional ‘life of.’”

—New York Times Book Review

“Tremendous . . . Birkbeck tells the epic of Sammy Davis, Jr. . . . from his Harlem boyhood to his wrenching deathbed (he died of cancer in 1990) in his Beverly Hills mansion, where various hangers-on, seeing the circling vultures, stripped his corpse even before it was a corpse.”

—Los Angeles Times Book Review

A BEAUTIFUL CHILD

“Matt Birkbeck created a beautiful masterpiece.”

—True Crime Book Reviews

A DEADLY SECRET

“Mr. Birkbeck presents a startling inside look at the politics of police work that can place roadblocks in the place of justice.”

—Westchester County Times

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA)

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group, visit penguin.com.

THE QUIET DON

A Berkley Book / published by arrangement with the author

Copyright © 2013 by Matt Birkbeck.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Berkley Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group.

BERKLEY® is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA).

The “B” design is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA).

For information, address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

a division of Penguin Group (USA),

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-101-61826-4

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Berkley premium edition / October 2013

Cover photo by AP Photos / Bufalino.

Cover design by George Long.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Most Berkley Books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales, promotions, premiums, fund-raising, or educational use. Special books, or book excerpts, can also be created to fit specific needs. For details, write: [email protected].

Contents

Praise

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

EPILOGUE

Sources

Photographs

For Donna, Matthew and Christopher, the loves of my life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A number of people helped make this book a reality, and special thanks go to my friend and former boss Peter Leffler, of the Allentown Morning Call, whose support and encouragement allowed me to follow this story; Nathanial Akerman, former assistant U.S. attorney in New York; Ralph “Rick” Periandi, deputy commissioner of the Pennsylvania State Police (retired); my attorney, Jay Kenoff, of Kenoff and Machtinger in Los Angeles, California, for his constructive counsel and continued support; and my editor, Natalee Rosenstein, who published my first two books and welcomed me back for a third go-round.

PROLOGUE

The old man with the droopy right eye sat slumped on the witness chair pretending to be a nobody.

At five feet ten inches and nearing eighty years of age, he sure didn’t look like anyone important, not with his ruffled suit and tired features. So it was hard to believe for anyone looking at him in the courtroom at the federal district courthouse in Manhattan in October 1981 that he could be a threat to anyone, much less be the man responsible for the murder of Jimmy Hoffa.

But federal prosecutors had circled around the old man following one of the most intense and thorough investigations in the history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. More than two hundred FBI agents were assigned to the Hoffa case within hours after the former head of the Teamsters union had vanished into thin air on July 30, 1975. Over the next three years, agents conducted hundreds of interviews and reviewed countless documents, and prosecutors convened several grand juries. In addition, there were two congressional hearings and a separate Senate committee investigation. But all were frustrated and doomed to failure by the lack of evidence and the inability to get any one of the alleged conspirators to talk, chief among them the elderly man now sitting on the witness stand, who preferred to discuss the joys of dipping fresh, crisp loaves of Italian bread into a well-made tomato sauce.

So, instead, the government agents took a different tack and harassed their suspects, a small group of men long affiliated with organized crime, charging them with anything they could in the hope of pressuring them to tell the truth but otherwise feeling content that getting them off the street and inside a prison cell was an acceptable alternative.

Rosario “Russell” Bufalino was no exception.

Jack Napoli ran to the FBI seeking their protection in 1976 after Bufalino threatened to personally strangle him with his bare hands. Napoli unwisely used Bufalino’s name to buy $25,000 worth of diamonds, and then bounced the check on the merchant, who subsequently sent word to Bufalino. Napoli was summoned to the Vesuvio restaurant, in midtown Manhattan, to explain himself. But it was Bufalino who did most of the talking, and everything he said, including the promise of what he would do to the six-foot-six, two-hundred-forty pound Napoli if he didn’t return the diamonds, was captured on a recording device Napoli wore, courtesy of the FBI.

“I’m going to kill you, cocksucker,” Bufalino roared, “and I’m going to do it myself and I’m going to jail just for you.”

Bufalino’s threat was somewhat prophetic. He was indicted on federal extortion charges, found guilty and served four years in prison, where he stewed over Napoli and remained so transfixed with the informant that he enlisted a cell mate to kill him. But the FBI found out about that plan too and charged Bufalino again, this time with attempted murder as he exited the prison.

The new charges didn’t bring any headlines. The media barely acknowledged Bufalino, who may have had business interests in New York, but he was, after all, from Pennsylvania of all places, which didn’t warrant the often rabid media attention heaped on other organized crime figures who hailed from Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island and New Jersey, such as “Crazy” Joe Gallo, Carmine Galante, Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino an

d his successor, Paul Castellano.

But there were a select few who knew about the old man, and among them was Nathanial Akerman, a young assistant U.S. attorney who had been prosecuting organized crime cases for several years and had access to the sensitive files detailing Bufalino’s history.

He first appeared on the FBI’s radar in 1953, when his name was mentioned in a secret report filed by the Philadelphia bureau as part of the FBI’s new “Top Hoodlum Program.” Over the next quarter century, Bufalino’s name continually resurfaced in the FBI reports, detailing his hold over the garment industry in Pennsylvania and New York; his control over Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters union, especially its rich pension fund; and Bufalino’s role in organizing the infamous meeting of organized crime chieftains held in Apalachin, New York, in 1957, the very meeting that finally introduced the Mafia, La Cosa Nostra, to America.

Akerman also had an inkling about Bufalino’s connections to the plots by the Central Intelligence Agency to kill Fidel Castro.

Some twenty years earlier, in April 1961, Bufalino stood on a boat with three other men—one an agent with the CIA—that drifted in the Caribbean off the Bahamas and just ninety-miles away from where a U.S.-trained force was about to invade Cuba. Bufalino was going to follow the invaders into Havana to retrieve nearly $1 million that he had hidden just before fleeing the island more than a year earlier, after Castro consolidated his power and assumed control of the island’s casinos, including two that Bufalino co-owned near Havana. Before fleeing Cuba, where he had been doing business for nearly twenty years, Bufalino had carefully wrapped the money in oilcloth and buried it. He left the island enraged, chain-smoking cigarettes as he watched the fading lights while his boat sliced through the waters of the Caribbean Sea during his hasty escape.

It was Jimmy Hoffa who had introduced Bufalino to the CIA, in 1959, and it was Hoffa who had also been the CIA’s go-between for two other gangsters, Sam Giancana and Johnny Roselli, to help in the agency’s covert operation to eliminate Castro. Giancana was the powerful head of the Chicago outfit, and Roselli, from Los Angeles, began his career as a contract killer for Al Capone but left Chicago in the 1920s to oversee organized crime’s control of Hollywood and later Las Vegas.

The CIA had used gangsters before, but Cuba was a natural, and tapping their anger over the loss of lucrative businesses seemed like a good idea. Cuba had long been their gold mine, gathering riches from the casinos, brothels, drugs and legitimate businesses that poured into and out of Havana. Organized crime lavished in the kind of wealth it hadn’t seen since Prohibition.

Bufalino, then fifty-eight, had for years been a regular visitor to Cuba, where he had stakes in the Havana casinos, a dog track, shrimp boats and several other businesses. And he counted his success in great part to his long-standing relationship with Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. The two men had met in the 1940s and enjoyed a number of mutual interests, in particular a love of money.

In fact, organized crime earned more than $1 million a day from its Cuban operations. It was a joint venture with a friendly government, only now that government was gone, and in its place was an idealist and revolutionary in Castro, who initially agreed to allow the crime lords to keep their businesses but later reneged, which is why the CIA reached out to Hoffa to enlist his organized crime partners to help eliminate the new Cuban leader.

The message was simple: President John F. Kennedy had approved air cover for a large invasion force to storm the island and ultimately overthrow Castro. But on the day of the invasion, the expected air support never materialized and the attacking force of less than two thousand CIA-trained soldiers, mostly Cuban exiles, was easily defeated. The Bay of Pigs was a military and political disaster, an embarrassment that would haunt America for decades, and Bufalino returned to the United States empty-handed.

Years had passed, and few knew the exact details of the CIA’s recruitment of gangsters in its Cuban operations until 1975, when Time magazine reported the agency’s ties to Bufalino, Giancana and Roselli. The information had spilled during a new Senate investigation led by Senator Frank Church of Idaho into the CIA’s assassination efforts in Cuba and elsewhere. One Time story, from June 9, 1975, relayed how Bufalino and two of his associates, James Plumeri and Salvatore Granello, had left large amounts of money behind after the Communists took over.

On June 19, 1975, ten days after the Time story was published, Giancana was preparing a midnight snack of sausages and peppers for himself and a guest in the basement kitchen of his home in suburban Chicago. At age sixty-seven, Giancana had recently returned from a self-imposed, eight-year exile in Mexico and was far removed from the vast criminal empire he once controlled. Long replaced as the head of the Midwest mob, Giancana sought a quieter life, which included the pleasure of frying sausages in oil for a friend.

But as Giancana stood over the stove tending to his late-night meal, his visitor aimed a .22 handgun equipped with a silencer behind Giancana’s head and pulled the trigger. The visitor then rolled Giancana’s lifeless body over onto his back and fired six more times around Giancana’s mouth.

Six weeks later, on July 30, 1975, Jimmy Hoffa sat in a suburban Detroit restaurant awaiting a visit from Tony Provenzano, a New Jersey Teamster official and highly regarded and powerful member of New York’s Genovese crime family. Hoffa had been paroled by President Nixon in 1971 after serving several years in prison for conspiracy, and he was seeking to recapture the Teamsters presidency. He first needed to settle several lingering issues with Provenzano. But Provenzano never arrived, and Hoffa vanished.

A year later, on August 9, 1976, Johnny Roselli’s decomposed body was found inside a fifty-five-gallon drum floating in a Florida bay. Roselli, seventy-one, had been strangled, shot and tortured. His legs had been sawed off, most likely while he was still alive.

Investigators originally believed the murders were the result of mob-related business. Organized crime figures didn’t exactly welcome Giancana’s return to Chicago, and Hoffa had irritated mob chieftains with his insistence in regaining the Teamsters presidency following his release from prison in 1971.

Hoffa threatened to expose their secrets at a time when organized crime’s relationship with the Teamsters was never better, under the leadership of President Frank Fitzsimmons, Hoffa’s handpicked successor. Tens of millions of dollars in loans from the Teamsters Central States pension fund flowed into new mob-controlled casino construction in Las Vegas and other projects, and Fitzsimmons had enjoyed a profitable relationship with President Nixon, offering his administration full Teamster support, and maintained his strong ties with the Republicans after Nixon’s resignation, in 1974.

Despite warnings from high-level organized crime figures to remain in the background, the bombastic Hoffa wouldn’t quit. When he disappeared, the investigators presumed he picked the wrong battle and his stubbornness led to his death.

It was the murder of Roselli that added a new, unexpected wrinkle. The Church Committee was also probing the CIA’s links to the Kennedy assassination, in 1963, along with its efforts to kill foreign leaders, including Castro. During the hearings, which began in 1975, the CIA shocked the nation by surprisingly admitting to its use of gangsters to help kill Castro. The committee, seeking to learn the truth, wanted to talk to Giancana, Roselli and Hoffa.

And then came the Time article, which included the first-ever mention of the secretive and reclusive Bufalino.

When the committee issued its final report on the CIA’s connection to organized crime, in 1976, its frustration ran deep, blaming the unsolved murders of Giancana, Hoffa and Roselli for its incomplete report and inability to discover the truth.

The CIA publicly denied any role in the murders or Hoffa’s disappearance, which produced an investigation the likes of which the FBI hadn’t pursued in years. Within a year, there was but a handful of chief suspects, all with affiliations either to the Teamsters or organized cr

ime or both.

And at the top of the list was the relatively unknown figure from northeast Pennsylvania, Russell Bufalino.

So, as the old man awaited his grilling inside the federal courtroom in April 1981, Nathanial Akerman approached him wanting to talk about Hoffa and the Teamsters, about Cuba, Castro, the Kennedys and the Bay of Pigs. But the prosecutor was relegated to the case at hand, which was nothing more than Bufalino threatening to kill a nobody who used his name to steal some diamonds.

“Now, it’s true, is it not, that you are a member of La Cosa Nostra?”

“No, sir.”

“It is true, is it not, that Carlo Gambino was a member of the La Cosa Nostra?”

“I don’t know about Carlo Gambino’s memberships.”

“You knew Carlo Gambino, right?”

“Yes, I did.”

Akerman then showed Bufalino a photograph of Frank Sinatra standing with several men following his September 1976 concert at the Westchester Premier Theater, a venue north of New York City.

“Mr. Bufalino, do you recognize anybody in this photograph?”

“I recognize Sinatra.”

“Do you recognize anybody else?”

“Carlo Gambino, and this is Greg DePalma with hair and this here is Castellano.”

“That is Paul Castellano?”

“That’s right.”

“You also know a Mr. Angelo Bruno, do you not?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Did you ever go to a meeting in Apalachin, New York?”

“I had charge of maintenance of Canada Dry Beverage, which was owned by Mr. Joseph Barbara.”

“I asked you a question. Did you ever go to a meeting in Apalachin?”

“There was no meeting. I was called at a house there anytime there was a breakdown or to deliver some groceries for my boss. I’d been there many times.”

“Do you recall any particular date that there were a number of people there?”

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino