- Home

- Birkbeck, Matt

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino Page 3

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino Read online

Page 3

To keep their information secure and help the administration avoid a potentially embarrassing controversy, Periandi suggested that the state police simply make a recommendation as to Friel’s fitness to hold the position. The administration nixed that idea, and Friel remained the chairman. But when the background investigation was completed, just after Labor Day 2004, Periandi went to Miller with the grim news.

“The administration will be concerned if this Friel report gets out,” said Periandi. “I think the way to get around this is for the administration to tell Friel to step back from the appointment.”

Miller brought the suggestion to Rendell, and the reply was swift: Friel would not step aside. In addition, Rendell wanted to see the full state police report. But the allegations, which were supposed to be confidential, surfaced in the Philadelphia Daily News, and Friel, who vehemently denied any wrongdoing, was forced to step down as chairman less than a month after he was appointed.

Friel’s resignation infuriated Rendell, who during an emotional press conference publicly lashed out at the media for publicizing the allegations.

“You’ve unfairly tarnished the reputation of a good and decent man,” said Rendell, with tears in his eyes. “I hope you understand what you did.”

But it wasn’t the media that drew Rendell’s wrath. Privately, he seethed at the state police and blamed the police for leaking their report. It was a fiasco that not only embarrassed the administration, but created much larger problems for future Rendell appointments. If Rendell’s first gaming appointment could easily get blown out of the water, how would other favorite candidates and appointees with checkered histories pass police muster, especially those seeking gaming licenses, such as Louis DeNaples? The solution came in a report that Greg Fajt and the Department of Revenue had commissioned from a consultant six months earlier.

Spectrum Gaming was a New Jersey firm headed by Fred Gushin, a respected gaming authority and a former New Jersey assistant attorney general. Tasked by Fajt and the Rendell administration with creating the foundation of the new gaming industry, Gushin produced a “Blueprint for Gaming.” The one-hundred-plus-page report was submitted in October 2004, and among Gushin’s many recommendations was tasking the state police with overseeing the all-important background checks. But just days after submitting his report, Gushin was told to immediately stop work and turn over all documents relating to its assignment. No one knew what was going on until December, when Gushin learned that Fajt had changed his report. Among Fajt’s recommendations was the creation of a new agency—the Bureau of Investigations and Enforcement (BIE)—that would be under the control of the gaming board, and would supplant the state police and conduct all background checks. The police role was reduced to performing low-level background checks and overseeing casino security.

Gushin was furious that the administration would pass off the new recommendation as his work product, and he fired off a letter on December 9, 2004, to the new gaming board chairman-designate Thomas “Tad” Decker, a well-connected attorney and partner with the powerful Philadelphia law firm Cozen O’Connor.

“This report does not reflect our work product and we do not concur in its recommendations and conclusions,” wrote Gushin.

The decision to replace the state police with BIE also stunned Periandi and Miller. Their relationship with Fajt had grown cold, but they had no idea just how frosty it had become. In retrospect, although they thought they were doing their jobs in ferreting out Friel, they derailed Rendell’s first nomination, which was a mistake the governor wouldn’t make twice. By giving background investigations to BIE, the gaming board would effectively control the investigative process, especially for favored casino applicants. But BIE was a civilian agency, and even though it would be stocked with former law enforcement personnel, they would not be privy to the kind of deep, classified criminal information available only to law enforcement agencies, such as the state police or FBI.

That meant anyone applying for a gaming license in Pennsylvania would not be fully vetted.

It was a disaster in the making, and none of this made any sense to Periandi. And as he pondered the administration’s actions, another unsettling issue was developing, and this one had to do with Louis DeNaples.

TWO

Once a jewel that for decades drew vacationers from the New York metropolitan area eager to lap up the country air, good food and celebrity entertainment, Mount Airy Lodge had, by the 1990s, lost its luster. Plagued by financial difficulties, the resort closed in 2001 after its owner committed suicide, and it was taken over by a private-equity firm, Cerberus Capital Management, which later sold it to Louis DeNaples, in 2004.

Periandi first heard about DeNaples in the early 1980s, when his name surfaced in several Pennsylvania Crime Commission reports. DeNaples, according to the reports, had close associations with the Bufalino crime family, which in its heyday was only fifty members strong yet controlled all organized crime activity in northeast Pennsylvania and parts of southern New York State. Among its favored businesses were loan sharking, extortion, money laundering, labor racketeering and prostitution.

According to the crime commission reports, DeNaples’ relationship with the Bufalinos was publicly unveiled after he pleaded no contest in 1978 for defrauding the U.S. government for taking part in a scheme that fraudulently billed more than $500,000 for supposed cleanup work from Hurricane Agnes, which devastated the region in 1972. DeNaples was charged with several other men, including Scranton city officials, but the trial ended in a hung jury, with one lone holdout forcing an acquittal. Prior to a second trial, DeNaples pleaded no contest to a single fraud charge. He paid a $10,000 fine and was placed on probation but escaped a prison sentence.

But in 1980, the FBI was tipped off that the first DeNaples’ trial had been fixed by several members of the Bufalino family, among them James Osticco, the underboss and a hard-core gangster whose relationship with the family namesake, Russell Bufalino, went back to the 1950s. Both men had been arrested at the famed mob gathering in Apalachin, New York, in November 1957, which for the first time brought organized crime out into the national public eye.

In 1983, Osticco and several others were tried and convicted for bribing the juror and her husband. The price was cheap: $1,000, a set of car tires and a pocket watch.

The DeNaples case was subsequently referenced in several Pennsylvania Crime Commission reports, as were his alleged ties to Osticco and several other organized crime figures, among them William D’Elia, who had taken over leadership of the Bufalino family in the mid-1990s.

The DeNaples story was the legendary rags to riches. His father, Patrick, was a railroad worker, and DeNaples grew up piss poor, sharing shoes and other clothing with his siblings. As a young man, he sold Christmas trees on a corner lot, using his profits to buy a single junked auto. Some forty years later, DeNaples led a billion-dollar legacy that included ownership of two of the largest garbage landfills in Pennsylvania and several auto junkyards and appointments to some of the region’s most prestigious boards, including the University of Scranton and Blue Cross Blue Shield, where he rubbed elbows with some of the most-respected and well-known names in the region. He also had his own bank, First National Community Bank, where he served as chairman and was the largest stockholder.

By the 1990s, everyone in the region and in the wide halls of the capital in Harrisburg knew about DeNaples, who aside from being a shrewd businessman attended mass daily and was a major benefactor who gave away millions to local charities and the Catholic Church. DeNaples’ donations were legendary, including a $35 million gift to the University of Scranton for a gleaming marble building named after DeNaples’ parents. His philanthropy helped him gain wide support among not just the local populace, but the entire political infrastructure. DeNaples also cultivated deep ties within state and federal government and counted figures such as Pennsylvania senator Arlen Specter as friends. He also had wel

l-entrenched associations with law enforcement, so few people dared oppose him.

As Periandi ascended through the police ranks, he would often hear about DeNaples, but not for his charitable pursuits. Aside from the Pennsylvania Crime Commission reports, DeNaples’ name had surfaced on occasion. In 2001, a federal affidavit directly connected him to William D’Elia. Known as “Big Billy” for his hulking six-feet-four-inch frame, D’Elia was once Russell Bufalino’s driver and bodyguard whose notoriety earned him a lifetime ban in 2003 from the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement from entering any Atlantic City casinos.

Following Bufalino’s death, in 1994, it was D’Elia who eventually gained control of the family, and according to the 2001 affidavit, several confidential informants alleged that DeNaples had made payments to D’Elia for undisclosed work and protection. No charges were filed against D’Elia or DeNaples in connection with this investigation.

Periandi had enough of a working understanding of DeNaples to know of his wide influence within the state, particularly its political circles, and he was disturbed that DeNaples was seeking a gaming license. Even more disconcerting was the language in the new gaming legislation, which barred convicted felons from owning casinos unless the conviction was older than fifteen years. DeNaples’ 1978 conviction, ironically, was more than twenty-five years old, which qualified him for a license in Pennsylvania but not in other gaming states, such as Nevada or New Jersey. In addition, Periandi couldn’t help but notice that DeNaples’ purchased the Mount Airy property before he was even approved for a slots license.

Something was clearly amiss, and no doubt, Periandi believed, the DeNaples entrée into gaming was one of the primary reasons why the state police were cast aside: DeNaples was certain to get a slots license. Given DeNaples’ history, Periandi believed that a routine state police investigation should have blocked any chance of him owning a casino. But with the police now out of the picture, there was nothing to stop the gaming board from eventually granting DeNaples a casino license.

But to make that happen and gain final approval for DeNaples and any other potential licensee with a questionable history supported by the Rendell administration, Periandi theorized that it required the participation from not only the gaming board, but possibly the leaders of the state legislature and the Rendell administration.

By 2005, as the state was moving ahead with its gaming initiative, Periandi felt more uncomfortable with the entire effort and decided it was time to take a closer look. But he needed a partner. The dichotomy of Pennsylvania state politics afforded few secrets, even within law enforcement. Periandi didn’t have any faith in the state attorney general’s office, which no doubt would have quickly signaled to Rendell that something was afoot. At best, the understaffed attorney general’s office would simply have meddled in the probe and produced a half-assed investigation that may have resulted in a few allegations but end with no charges.

Periandi also had issues with the U.S. attorney’s office in Harrisburg, which was part of the Middle District, which included Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, DeNaples’ home turf. So Periandi made a single phone call, and on April 28, 2005, he left his office in Harrisburg and headed to FBI headquarters in Philadelphia.

When he arrived, waiting for him inside a large conference room were Jack Eckenrode, the senior special agent in the Philadelphia office, and John Terry, the special agent in charge of public corruption. Joining them were half a dozen other special agents from Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, Erie and Scranton. Eckenrode quickly gave the floor to Periandi, who opened the meeting by explaining how he suspected that Rendell, members of his administration and others in state government might be trying to control the new gaming industry in Pennsylvania.

Periandi recapped the previous twelve months, including the Friel investigation, and to further make his point, he said that just two days earlier he and Petyak had met with members of the Gaming Control Board, including its chairman, Tad Decker, to again discuss the future state police role. But Decker and the board had little use for the police and made it clear, again, that the gaming board would rely on its own BIE for critical background investigations of all casino applicants. Of particular interest to Periandi was the sudden addition of attorney William Conaboy to the gaming board. Conaboy was one of DeNaples’ attorneys in Scranton and had served on several boards with him.

Periandi said he had also become aware of another potential issue. The Rendell administration had hired a Rhode Island firm, G-Tech, to oversee the implementation of the central computer system that would eventually have primary control over each of the sixty thousand slot machines in the state. The contract to create and oversee the computer system ran into the tens of millions of dollars, and Periandi was floored when he learned that G-Tech was populated with executives who previously served in high positions under Rendell when he chaired the Democratic National Committee (DNC). Among them was Donald Sweitzer, a G-Tech vice president who was a twenty-year member of the DNC and its former political director and a fund-raiser. And Kenneth Jarin, a fund-raising chairman for the DNC, was hired by G-Tech as a consultant. Jarin was one of Rendell’s partners at his old Philadelphia law firm Ballard Spahr and a close aide who was Rendell’s biggest fund-raiser for his 2002 gubernatorial run.

Given the numerous players involved, Periandi said he couldn’t conduct a public corruption probe of this magnitude on his own. He just didn’t know how deep into the rabbit hole he’d have to dig to potentially flush it out, and he needed the FBI to be a partner. The state police would do the heavy lifting, Periandi said, and he even surprised those in the room with the disclosure that he had his own “Black Ops” team of covert investigators that reported directly to him. No one outside of Periandi’s small group would know about the investigation, he said, not even the commissioner, whom Periandi said required “plausible deniability.”

“If we establish a lead but can’t pursue it, then I want to know I can turn to you to run with it,” Periandi said.

To Periandi’s surprise, Eckenrode agreed. The FBI, said Eckenrode, had already initiated its own public corruption probe of Pennsylvania politicians. Eckenrode wouldn’t disclose who was under investigation, but he shared Periandi’s opinion there were major concerns with the gaming initiative and a joint effort would be beneficial to both the state police and FBI. Periandi did not know if the FBI was looking at Rendell, but the most likely candidates were members of the state legislature, perhaps Vince Fumo. Periandi knew, for instance, that the longtime Senate leader had several prior unpublicized brushes with the law, including a state police investigation into falsified applications to the state Liquor Control Board from several nonprofits with ties to Fumo. The FBI had also been looking into the matter, which prompted Periandi and the state police to move aside.

There was also Robert Mellow, who had been a member of the Senate since the 1980s and, like Fumo, had integrity issues. Periandi became familiar with Mellow from his days serving as commander of Troop N, a busy hub in Hazleton that oversaw much of northeastern Pennsylvania, from the Poconos up through Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, which was part of Mellow’s district.

Mellow had once been under federal investigation for allegedly taking kickbacks from Mount Airy Lodge during the 1980s, though no charges were ever filed. He was also a very close confidant of Louis DeNaples. They were so close that the two men would meet regularly, often going for private walks to discuss business and other matters of interest.

With the FBI on board, the task force was formed, and Periandi would quietly begin his investigation, with Governor Ed Rendell and his administration as the chief targets. Upon returning to Harrisburg, Periandi immediately shared the news with his small “Black Ops” team, which included one of his most-trusted members, trooper Richie Weinstock.

Weinstock was a former narcotics detective who was handpicked by Ron Petyak as an original member of the state police gaming intelligence unit t

hat was formed after the legislation was passed, in July 2004. Weinstock had grown up in the Scranton area, and he knew the history of the region, including the wide influence of the Bufalino family. Lackawanna and Luzerne Counties, home to Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, respectively, were by even the lowest of standards places where corruption was endemic and an accepted part of everyday life. From the old Kefauver Committee of the 1950s, one of the early federal investigations into organized crime that determined law enforcement in the region to be utterly “blind” when it came to prosecuting gambling, to the later convictions of major political figures such as the popular congressman Daniel Flood, of Wilkes-Barre, in the 1970s for taking payoffs, and the state attorney general Ernie Preate, of Lackawanna County, in 1995 for mail fraud.

The entire region, from Scranton to Wilkes-Barre, had long been thought to have operated in its own vacuum, where the crooks were the good guys and everyone else looked the other way.

Weinstock was a charmer, with a loud, outgoing personality and intensity and talent for detective work. It was Weinstock whom Periandi first tasked with quietly conducting secret background checks on members of the Rendell administration, including John Estey and Greg Fajt, after the gaming legislation was approved. Apprised of the new probe, Weinstock was given strict orders that the gaming investigation would be “off the line,” meaning there was no direct chain of command other than he reported to Petyak, who reported to Periandi.

Nearly three years later, the fruits of that investigation began to bear out with the stunning indictment of the Rev. Joseph Sica, who was charged with lying to a grand jury impaneled the previous summer in Harrisburg to investigate DeNaples and determine if he had lied to the gaming board about his mob ties.

As expected, DeNaples had been awarded a slots license in December 2006, despite warnings from Periandi to Tad Decker and the gaming board that there were issues. Periandi couldn’t say why, so the board ignored him and went ahead and approved DeNaples anyway. Two months later, the state police took their case to Ed Marsico, the district attorney for Dauphin County in Harrisburg, who impaneled the grand jury in April 2007 to investigate whether DeNaples lied to the gaming board about his alleged mob ties.

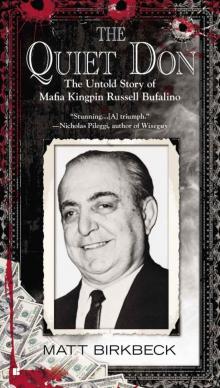

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino

The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino